It’s 1987, on a dark and muggy September night in central Brazil. Two men approach a partially demolished abandoned medical site. The two men are Roberto Alves, the owner of a scrapyard, and his friend Wagner Pereira. To their surprise, the lone security guard usually posted on duty is nowhere to be seen. With the coast clear, they illegally enter the site and begin scavenging for anything of value.

The abandoned medical institute is in Goiania, a city of about 1.5 million people, two hours from the country capital of Brasilia. The hospital was formerly run by a private medical company called IGR, who had since moved to a new location two years prior in 1985. In doing so, they had left various equipment and supplies behind. The site became tangled in extensive litigation between IGR and the Catholic organization that owned the land and the building. Eventually, a court order was issued preventing IGR from accessing the abandoned site. With only a single guard on duty, it soon fell into disrepair and became a popular place for opportunists to break in and swipe the remnant valuables.

On that fateful night, Alves and Pereira found a large machine in one of the abandoned rooms. Unsure of what it was, they deduced from its weight that there was a good chance of finding precious metals inside. They partially disassembled the machine and extracted the heavy core capsule. They loaded it onto a wheelbarrow and departed.

Photograph of the capsule stolen by Alves and Pereira.

Once back at Alves’ residence, the pair quickly got to work attempting to disassemble the unit they had stolen, though it turned out to be much more difficult than they initially thought. They were initially cautious, as they didn't want to risk damaging anything expensive inside that they could sell later. Later that day, they both had to stop, as neither one was feeling well.

The next day, Pereira would feel even worse. He was vomiting, had severe diarrhea, and felt dizzy and faint. He also felt an intense burning sensation on his hand. The next day, he checked into a local clinic, where they diagnosed him with food poisoning and told him to go home and rest.

In his book Into Thin Air, the author, Jon Krakauer, painstakingly details his journey to climb Mt. Everest in 1996 with one of the increasingly popular guided tour groups of the time. These groups promised that well-paying customers would reach the summit, even those who had minimal mountaineering training.

For Krakauer, what started out as a simple writing assignment from an outdoors magazine turned into a fight for his life. His group, along with several others, were caught in a massive blizzard near the summit of the tallest mountain in the world. A climate and conditions that, on a calm day, are already not meant for humans to survive in. Many people died that day, and the resulting book from Krakauer is an analysis of what went wrong, and moreover, an attempt to reconcile his part in it.

In his analysis, Krakauer says “...as the events of 1996 demonstrated, the strongest guides in the world are sometimes powerless to save even their own lives. Four of my teammates died not so much because (our) systems were faulty--indeed, nobody's were better--but because on Everest it is the nature of systems to break down with a vengeance.”

When subjected to analysis, it becomes clear that many of the disastrous events in human history are the result of a gradual breakdown in systemic process. And not due to one big mistake, but a series of small, seemingly inconsequential errors that over time can compound into disaster.

Unknown to them, the seemingly inconsequential legal squabble between IGR and the landowners of the Goaiana institute had already laid the seeds of catastrophe.

While Pereira was resting, Alves continued to tamper with the strange capsule. One end contained a circular aperture that Alves was able to eventually puncture and create a small opening. When he peered inside, he saw something incredible. There was light coming from inside. An entrancing deep blue phosphorescent light.

Now, even more convinced of its value, Alves inserted a screwdriver in the opening and removed a bit of the glowing substance. To his surprise, it was a fine powdery sand. To him, it was a marvel. He tried to light it on fire, unsuccessfully, thinking that perhaps it was a type of gunpowder. Though he had successfully accessed the interior of the capsule, Alves deduced that whatever it and the glowing contents inside were, they were out of his area of expertise.

Two days after puncturing the aperture, Alves sold the capsule to another scrapyard, run by Devair Ferreira. Devair was also fascinated by the glowing powder inside, though unlike Alves, attributed it to a more divine source. He brought the capsule into his house and invited all his family and friends over to view it.

On September 21st, three days after purchasing the capsule and eight days after its theft, one of Devair Ferreira’s workers was able to extract more of the substance from the unit. Excited, Ferreira began to share it with his friends and family. That very same day, Ferreira’s wife, Maria, began to feel sick.

One of the recipients of the gleaming powder was Devair’s brother, Ivo. Ivo took some of the powder to his house a short distance away and spread it on the concrete floor. His six year old daughter, Leida, was especially fascinated by it, and would rub it on skin and clothes like war paint to show off to her mother.

On September 25th, Devair sold the capsule again to a third scrapyard. His wife Maria, now seriously ill, was the first to piece together that something was very wrong. Many of their workers, friends, and family were all falling sick at the same time. Correctly guessing that the stolen capsule and its strange contents were to blame, she repossessed them from the other scrapyard and immediately brought them to a nearby hospital.

Little did Maria know at the time, she was already dead.

For the power that gave the sand its hypnotizing glow was neither mystical or divine. It was deadly. It was radiation.

Radiation is one of the most terrifying and devastating hazards for living organisms. It’s unavoidable and everywhere. It’s in the air you breathe, the food you eat, the dirt, your cellphone, the very light from the sun we depend on. You can’t see it, hear it, smell it, or touch it. It’s all but invisible, except when it’s not.

But what exactly is radiation? When we say a material, like the glowing sand, is radioactive, what that means is that in its current form and in its current environment, the very atoms that make up said material are in a configuration that is not stable. In order to become stable, the atoms must shed some of themselves. This shedding takes the form of incredibly miniscule particles that rocket away from their atoms in a random direction, faster than a bullet from a gun. There is a scientific measurement for this. If a radioactive material sheds one particle every second, it’s called a Becquerel.

The beautiful and captivating luminous blue powder in Goaiana, coveted by the ill-fated families and workers alike, was a radioactive salt of the element Caesium. It was radiating at a rate of 74 Terabecquerels. In other words, it was shedding 74 trillion particles every single second.

Radiation danger comes from these particles and their energy levels. Some forms of radiation throw off slower, heavier particles known as alpha and beta, equivalent to a rock from a slingshot. These can be harmful but their low energy doesn’t allow them to penetrate surfaces very well. For example, a single sheet of paper is enough to block alpha particles. Other forms of radiation take the form of electromagnetic photons. Light itself is a very low energy form of radiation. Ultraviolet light, harmful in the form of sunburn, is electromagnetic radiation.

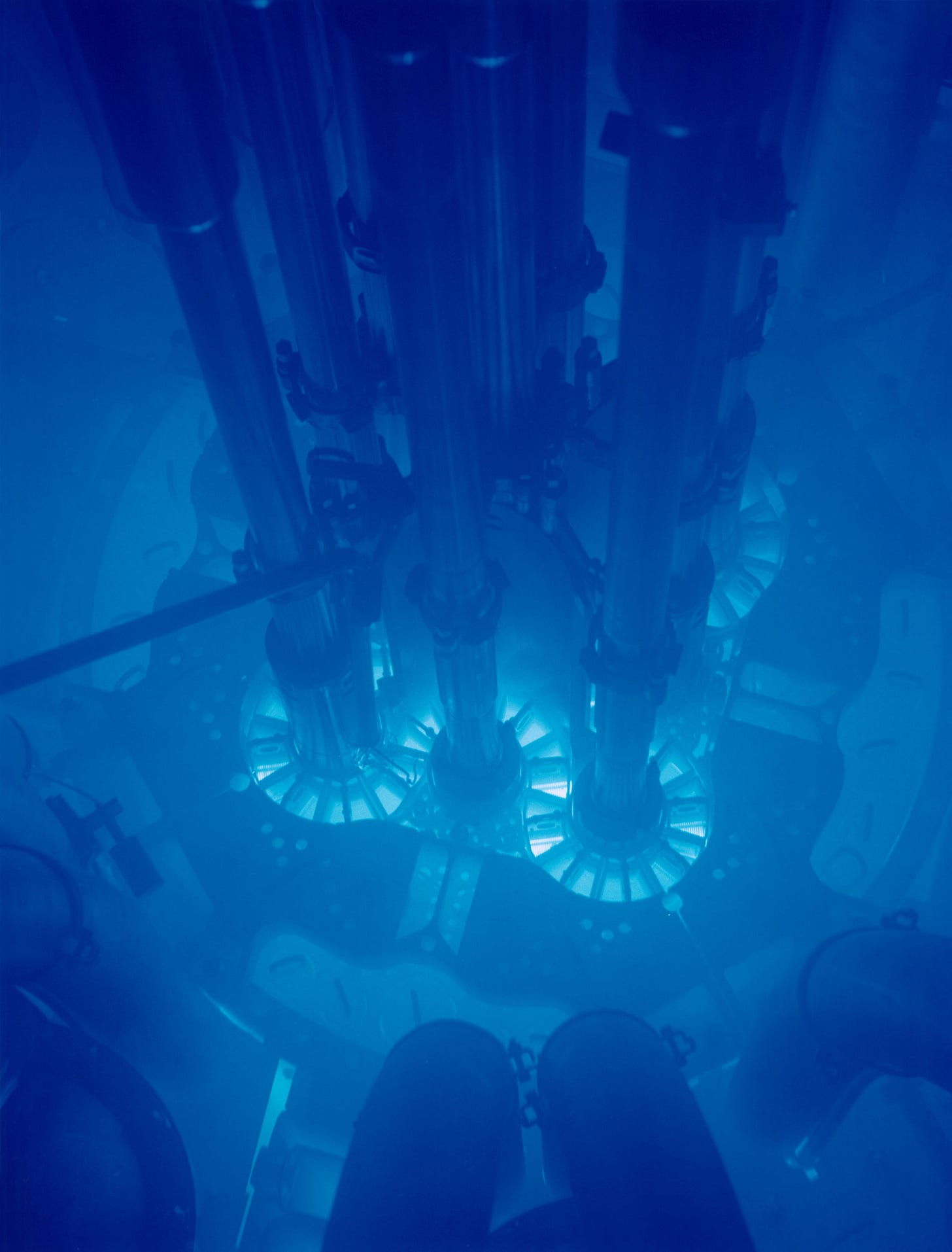

At the top of the electromagnetic energy spectrum is gamma rays. Gamma rays are extremely high energy, which allows them to easily penetrate through anything other than very heavy metals like lead. This makes them far and away the most dangerous type of radiation. Gamma rays are so powerful that they can ionize the very air molecules that they pass through, causing that air to glow with a haunting blue light, as seen from a nuclear reactor below:

Unfortunately for the people of Goiania, this phenomenon is exactly what they were witnessing from the sand in the stolen capsule.

On September 29th, the morning after Maria Ferreira brought the stolen capsule into a hospital, a visiting physicist used sensitive equipment to confirm the presence of radioactivity. He immediately persuaded local officials to take action as soon as possible. A full investigation and mitigation plan was put into effect, and an international hazard team was assembled.

News of the incident rapidly gained media attention worldwide. Panicked citizens of Goaiana flooded nearby hospitals to the tune of over a hundred thousand to be checked for exposure. In the end, 250 people were found to have some level of contamination, though most of it only minor.

Not so lucky was six year old Leida Ferreira, who had been rubbing the blue powder on her skin and clothes. When an international medical team arrived to treat her at the hospital, she had been confined; isolated and alone. The local medical staff were terrified to even get near her. In a very short time, she had already been disfigured, with body swelling, hair loss, organ failure, and massive bleeding.

One of the things that makes radiation such a sinister hazard is how unassuming the exposure itself can be. When a gamma ray photon encounters a living creature, it spears through them like a laser beam. This laser flies through the very cells that make up all organic tissue, and when they hit our DNA molecules, our genetic blueprints, it shatters them. Thus, breaking apart the critical instructions on how your own body should be put together.

This is all completely painless at first. Just like when you sit out in the sun for too long, unprotected, your skin cells are taking DNA damage, but you feel nothing. Even the redness and swelling that comes afterwards is not a direct symptom of the radiation damage you’ve received. Our remarkable bodies have methods to try and destroy and recycle cells with DNA damaged by radiation, to some extent. The red painful skin of a sunburn is inflammation as your body floods the area with immune cells to do just that, try and repair the damage.

Above a certain level however, the risks of long term damage become great. Most people are aware of how radiation exposure puts you at much higher risk of cancer. The DNA damage results in mutated cells that might not work as they should, with malignant results. But exposure at levels even higher than that, exposure from gamma rays…well, your body can only repair so much. These invisible knives have already done their damage, and there is nothing that can be done to save you. From that point on, you are a living corpse, until the body breaks down completely. Without hyperbole, this is truly one of the worst ways to die.

On the 21st of May, 1946, a physicist named Louis Slotin was working in a lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico. He had been part of the team that had created the first nuclear weapons used in World War 2, and had continued his research ever since.

On this day, he was performing an experiment with a chunk of radioactive plutonium, when his hand slipped. This small mistake caused a “prompt critical” nuclear reaction, instantly filling the room with an incredible burst of gamma ray radiation. Witnesses to the event said “the air in the room crackled with a neon glow of blue, and we all had a sour and metallic taste in our mouths.”

Slotin immediately stopped the experiment, and the entire incident elapsed in no longer than a few seconds. Acutely aware of what had just transpired, Slotin made all of the staff in the room mark their positions on the floor with chalk, and using his knowledge of physics and chemistry, was able to calculate the dosage of radiation received by everyone in the room. He concluded that everyone would live.

Everyone, except himself. For himself, all he could say was, “I’m dead.” Nine days of agony later, he was proven right.

Unfortunately for Leida Ferreira, she too had been exposed to more than her young body could take. She died a month after her first exposure. Maria Ferreira was also one of the victims from the incident, passing away on the same day as her niece. So did Israel Santos, an employee of Devair Ferreira who had worked on extracting the material from the stolen capsule. And Alves, one of the original thieves of the device. His partner, Pereira, survived, but had to have some of his fingers amputated. As for Devair Ferreira himself, despite receiving a higher dose of radiation than any of the deceased victims, he managed to miraculously survive the initial event, though was plagued by many health complications for the rest of his life.

The Goiania cleanup effort became a massive undertaking. The radioactive caesium dust could dissolve in water, which meant there was a real danger of contamination into city or ground water that could exponentially worsen the situation. All plumbing near the contamination zones had to be opened and inspected. Industrial grade vacuums were brought in to suck up as much dirt and dust in the contaminated sites as possible. Roofs were vacuumed and hosed down, and in some cases removed entirely. All topsoil had to be removed, paint had to be scraped off walls, and floors and ceilings had to be sprayed with acid.

All of the small mistakes, by IGR, by the thieves, the landowners, the scrapyard workers, led to systemic disaster that cost innocent people their lives. Contamination incidents like Goiania, or in Chernobyl, or Three Mile Island, leave a lasting scar. Not just on the world itself, but on the psyche of the entire populace. Like the radiation, this takes a long time to heal. For Devair Ferreira, he not only lost his wife, his niece, and his own health, he lost everything. His scrapyard was ultimately deemed beyond saving, and was demolished completely. All that remains is the scar; an empty lot in the city, still feared by the locals to this day.

The empty lot that was once Devair’s scrapyard and home.

Even after all the cleanup, the legal battle over who was to blame had only just begun. The device that contained the fatal blue dust was determined to be part of a radiotherapy unit, used to control and deliver radiation to patients as part of cancer treatments. Its danger was known to IGR, but as they were barred from entering the site due to a dispute with the land owners, they could do nothing about it. There were fines levied on all sides, but in the end, no criminal charges were ever brought forward, despite the enormous harm done.

In November of 1987, six year old Leida was laid to rest at a local cemetery. She was so contaminated that she had to be buried in a special coffin shielded with fiberglass and lead. Her body will remain dangerously radioactive for the next three hundred years.